Early Bird Offer! Free tickets to meet independent experts at this summer's Build It Live

Save £24 - Book Now!

Early Bird Offer! Free tickets to meet independent experts at this summer's Build It Live

Save £24 - Book Now!BIPV stands for building-integrated photovoltaics, which is quite a mouthful, so we’ll stick to BIPV for this article. Like all forms of photovoltaic, these systems generate low voltage electricity from sunlight.

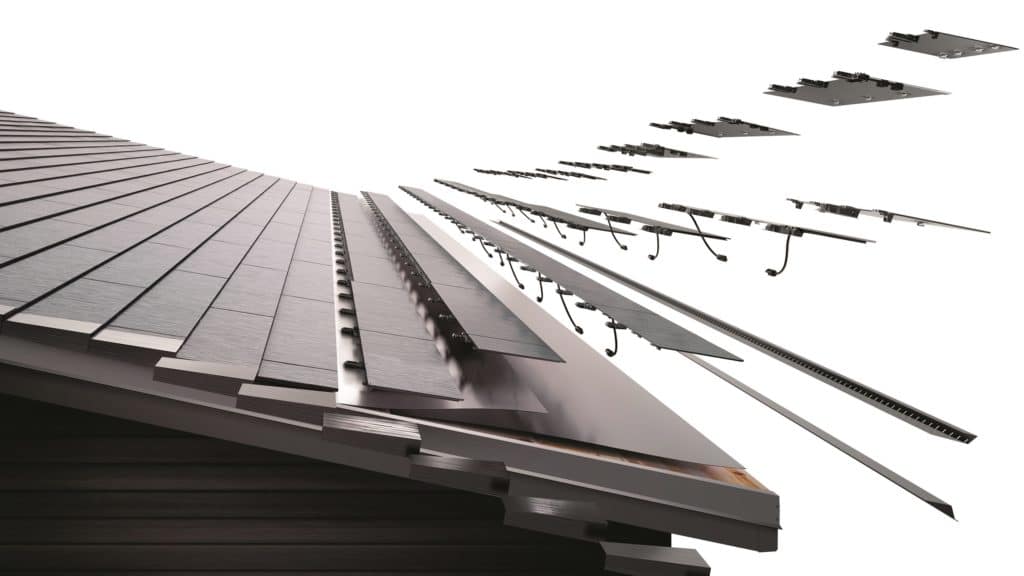

The integrated bit is the key. Rather than building a roof and then installing solar panels on top of it, with BIPV the modules are part of the roof covering. So, they’re keeping the building dry as well as generating power.

If you’re building a new structure, it makes no sense to construct a roof and then take it apart to bolt-on panels, so the majority of solar electric roof installations are now BIPV (ie built-in). There are two main types.

The more familiar is prefabricated PV modules, linked together with integral weatherproofing and drainage. The other is solar tiles (which, confusingly, look more like slates). Both of these systems can be installed on a wide range of pitches, which is important given the variation in roof design in new UK construction.

Read more: Government Announces 0% VAT on Heat Pumps, Solar Panels & Other Energy-Saving Measures

Walls can also be built in this way – replacing the outer rainscreen with PV tiles or modules. So, any suitably-oriented (and unobstructed) external wall can also generate power. However, it’s worth noting that when PV production is at its best (in the summer), the majority of useful light comes from a high incline – so vertical surfaces like this won’t be very good at collecting power.

For Build It’s Self Build Education House we installed sleek BIPV panels from Solarwatt and combined them with battery storage

For that reason, a wall will be much less efficient (per square meter) than a roof installation facing the same direction.

Many new homes are designed to include solar shading, such as projections or louvres, to keep out the summer sun. On that basis, you’d expect the building elements doing this job to have good potential for energy collection.

Indeed, solar sun shades are a great idea – and they can, of course, be designed to still let some light through if you wish. BIPV louvres can be fixed at the optimal inclination for solar collection, or they can be adjustable like Venetian blinds.

Beauty may well be in the eye of the beholder, but the general opinion seems to be that BIPV looks a lot better than bolt-on panels. When installed on a roof, the solar tile variety can integrate seamlessly with natural slates, so it is far less obtrusive.

Built-in modules, meanwhile, are designed to sit at the same height as the tiles – providing a sleek finish. A complete solar roof can look even better. BIPV also requires less of a margin around the edges of the modules than bolt-on BAPV (building applied photovoltaics).

Solar roof tiles, such as these from Tesla, are a wholesale replacement for standard roofing – allowing you to create a beautiful covering that contributes to powering your home

This not only looks better, but also increased the potential solar yield available from the roof area. Similarly, a well-designed solar wall can look really sharp. What’s more, as thin film can even be applied to curved surfaces, there is great scope for designers to get the best out of some unusual building forms.

When the roof or wall covering is replaced by a PV collector, then the PV module is doing the job of a roof tile or a rainscreen, so it’s keeping out the weather. In the sections where BIPV has been installed, then, you can omit the cost of that section of roof or external wall finish from your project.

So, in that sense it produces a saving. There is also a saving from not having to take apart the roof or wall to locate the fixing points necessary with bolt-on BAPV systems.

As BIPV modules have interlocking sections and integral drainage, they are a little more expensive per kWp (kilowatt peak) installed in comparison to BAPV.

| CLOSER LOOK: Thin film solar

This innovative type of BIPV can, in theory, be applied to almost any surface. This is different technology to the crystalline systems used in prefabricated panels. Instead, a membrane made of CIGS (copper indium gallium selenide) is laid over the substrate, such as a flat roofing membrane. Glazing can even be coated with thin film solar collectors, so that windows themselves become power generators. The membrane can be varied from fully to perhaps 50% opaque, depending on the elevation, height and location. Solar glass enables building designers to create some really interesting facades and turn curtain walling into an energy source. As you might expect, efficiencies are lower from solar film than for crystalline panels, but it does perform slightly better in low light conditions. We do not yet have good data on longevity, and given adhesives can break down over time in the UK’s widely varying climate conditions, this is an important question wherever glues are used to fix solar film to a substrate. Like all PV technology, efficiency drops as the solar collectors heat up, which will always be an issue for films adhered to thick substrates. |

But the saving on the relevant sections of wall or roof coverings helps to offset this. Solar tiles are also more expensive than panellised BAPV systems, and any PV on facades or similarly unusual applications will add cost, too.

Like applied PV panels, the electricity generated from BIPV is low-voltage DC current, so an inverter will still be required. Cabling and other installation costs are also broadly similar.

Read more: Solar PV Panels: Complete Guide to Home Solar Electricity

BIPV enables you to turn any appropriately-facing surface into a solar collector. So, broadly speaking, any wall which faces east, south, or west can generate some power, while south of course remains the best aspect.

This in-roof PV install by Spirit Energy uses SunPower panels and GSE mounting

There are efficiency losses from mounting PV on vertical surfaces such as walls, rather than the optimal 35-degrees from the horizontal, which is best angle for fixed panels in the UK.

As to whether BIPV is the future of domestic PV, that’s more questionable. It is certainly the most attractive and cost-effective way to integrate PV into a new building. For existing buildings, the prefabricated plant-on solar panels are likely to dominate for some time to come.

However, if you’re carrying out a roof replacement, for example, then it makes sense to integrate energy generation on suitable elevations – and in that case, BIPV seems to be the obvious way forward.