Building with Timber: Traditional Options

The timber frame method is hugely appealing for anyone wanting to build a house with traditional style but all the mod cons. Despite not having the bulk of a brick-and-block construction, timber frame is nevertheless strong, with good insulating properties.

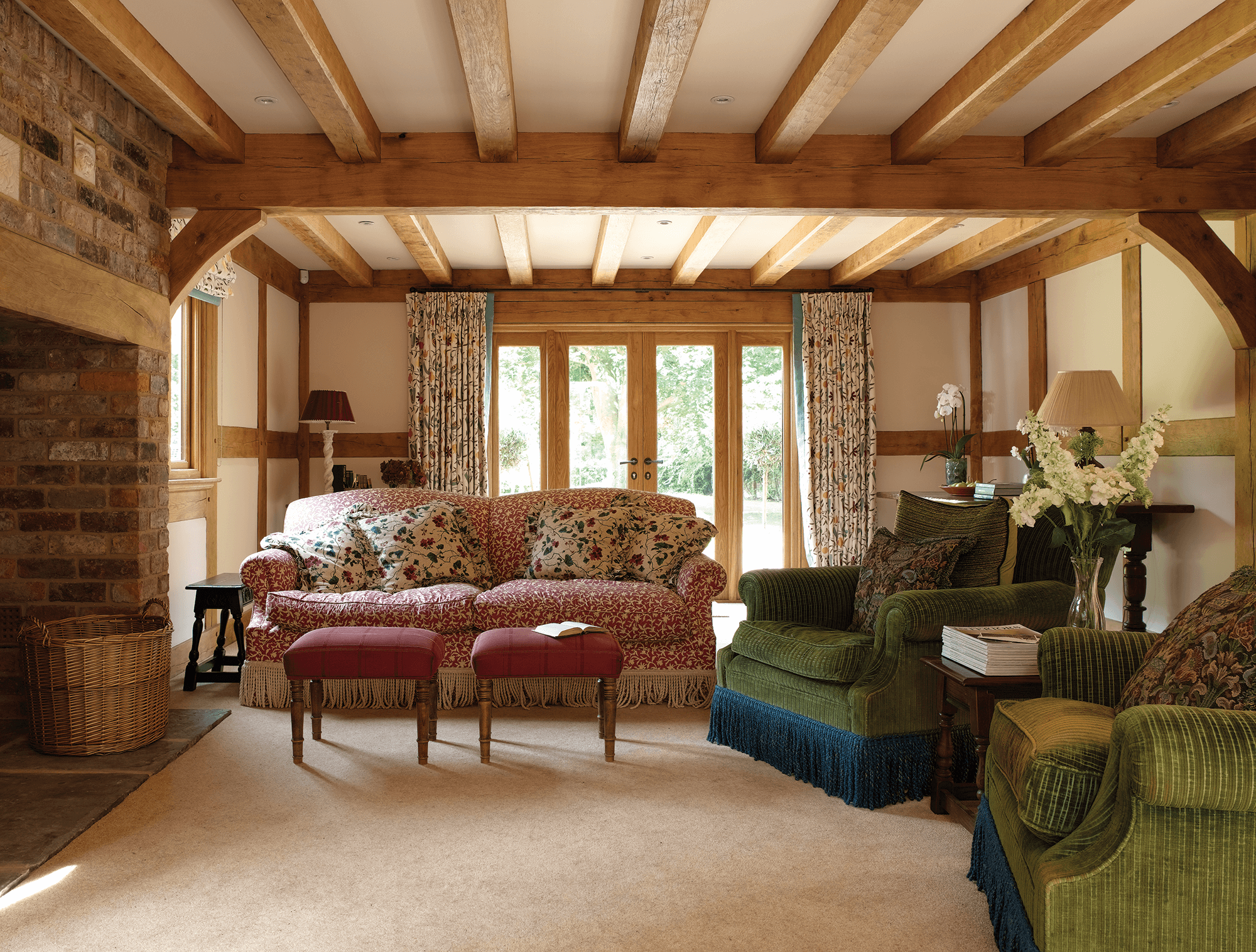

Since the structural timber frame takes the weight of the house, loadbearing internal walls are not required. That means interiors can be open plan and spacious with galleried landings, mezzanine floors and open roof structures to show off the beauty of the wood. Mortise and tenon joints fixed with oak pegs and left exposed are typical in traditional construction, with bracing supplied by curved beams.

The frame is prefabricated off-site and on arrival at the plot can be erected, roofed and made watertight within a few days so you’re less dependent on the weather to further the build.

Green oak

Oak’s strength, character and robust qualities have made it a favourite building material for centuries and, in these eco-conscious times, responsibly-sourced wood has the added advantage of being carbon neutral.

“A green oak frame is manifestly real. As it dries, it moves – with the movement accommodated by infill panel systems – creating gentle modulation in line and form of the timbers, giving oak frame buildings their sought-after character,” says Tim Crump, managing director of timber-frame package company Oakwrights.

The wood for these timber buildings is felled and used within two years, while it’s still green and has a high moisture content. At this stage it’s easy to work with. As it ‘seasons’, or dries and hardens, at around 25mm per year (or longer for thicker beams) the frame tightens, becoming stronger. At the same time, cracks will appear in the timber, but that’s all part of the charm and character of the material.

Infill options

Traditional timber-frame buildings had wall spaces filled with wattle and daub, a delightful mix of earth, cow dung and straw, supported on staves and woven wattles. It can still be used today, finished with lime plaster. Finishes include smooth trowel, roughcast and decorative pargetting, limewashed for protection. Herringbone brick is another authentic historic infill. Other alternatives include straw bales and structural insulated panels.

Roof

Thatch, the must-have of story books, has much to recommend it. Made from reed or straw, it is highly insulating, lightweight and flexible, but fitting it is a skilled job.

Tiles in stone, slate, clay or concrete are all options. As a finishing touch, substantial brick built chimneys and fancy chimney pots will give your build a medieval look.

Doors and windows

For a Tudor effect, opt for ledge and brace doors. It’s important to get both the proportions and the materials of the windows right, as they are a key design feature. And don’t forget that they have to meet Building Regulations’ minimum standards. Both dormer and mullioned windows can add to the ancient-building effect and, if you’re going for a period cottage look, remember that in the past windows would have been small and possibly varied in size. Leaded lights were common in the medieval period.

Main image: The Moores’ characterful self-build home features a post-and-beam frame by Border Oak (Photo: Jeremy Phillips)

Login/register to save Article for later

Login/register to save Article for later

Comments are closed.