Contemporary Coastal Self-Build

When Simon and Jane Crowther bought a bungalow in Fowey, Cornwall, nine years ago, they planned to do something with the old timber chalet at the bottom of their steep, clifftop garden.

Both properties had outstanding sea views, and initially, Simon considered extending the chalet. This plan gradually evolved into the decision to demolish it and build something new.

“We wanted to build to our spec, and we wanted something cheap to run, that we could just lock up and leave,” says Simon. “It’s such a fantastic location, why wouldn’t we make the most of it?”

Open design brief

Undeterred by a sloping site he likens to “the Cresta Run” and tricky access, Simon turned to local architects Atelier 3 with a tough brief: “astound” me.

- NameThe Crowthers

- LocationCornwall

- ProjectNew build

- StyleContemporary

- Construction methodTimber frame

- House size102m² (1,098 ft²)

- Land costAlready owned

- Build cost£268,900

- Cost per m²£2,636 (245 per ft²)

- Construction time31 months

- Current value£1.3m

Despite having worked as a builder for over 25 years, Simon’s experience is mainly in converting old farm buildings, and he felt that he needed a more creative input.

“I wouldn’t be able to get flowing lines; I wasn’t confident enough with a new build,” he says. “Ideas are what architects do best. You’d be silly not to use one.”

As there was such a broad brief, the design turned into quite a collaborative process, the final plans emerging through a series of 15 sketches.

“One of the things I wanted to achieve was a fusion of old and new – something that would dissolve into its surroundings,” says Simon.

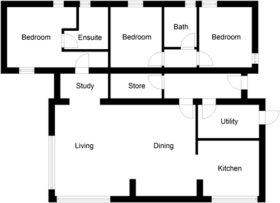

The outcome is a two-bedroom home (plus a one-bedroom annex) with an open plan living space that has sliding glass doors on two sides. A wide cedar soffit overhangs the upper storey, above a frameless glass balustrade, which shelters the master bedroom’s balcony.

These design features give the slate and cedar-clad home a quietly stylish appeal.

Getting planning permission

Simon expected planning permission to be a problem, so he took specialist advice from a consultant before talking to the council and, in particular, their conservation officer (the build is in a conservation area).

“I was keen to convey our vision for the house, which was something special, but not huge; something that would blend in, but with fine detail,” he says.

“With the planning process under way, I asked to speak before the local parish council, who I feel respond more favourably to individuals. Their approval was unanimous, and the application sailed through. The planning officer said that it was better than what was there before, and that’s the fact you really need to get across.”

With planning permission coming through in just a few weeks, Simon turned his attention to the groundworks. The first problem presented was access.

Constructing foundations

Perched between a tight residential cul-de-sac above and a narrow lane below, the solution was always going to be a creative one. The build inevitably ended up getting more physical, with most of the labour being done by hand, including carrying the concrete on site in buckets.

Before the foundations for the new house could be constructed, though, 1,600 tonnes of rock and soil were excavated, travelling down a chute to dumper trucks waiting on the lane below. The concrete for the 4m-deep reinforced retaining wall was pumped down via a long hose.

“The retaining wall has a ‘heel’, which comes halfway under the house’s foundations, and digging all this out was a marathon job,” says Simon. “We used steel and high-strength concrete to build the 75cm-thick wall.”

This was kept back using steel shutters that are normally driven directly into the ground. However, because of the rock on site, Simon was forced to strip 2m off the ground level, then dig down a further 3m, drill steel pins into the rock and backfill.

“It was a nightmare,” he says. “We anticipated three weeks, but it took three months – and cost £92,000.”

Trades and building materials

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Simon not only project managed the build himself, but also did most of the work, with the exception of the electrics, plumbing, and plastering. He also had a labourer on site to help him, and a digger driver during the groundworks phase.

“I felt I had time on my side, and took it easy. I was able to tweak and save money,” he says, but he warns others thinking of doing the same that, if you don’t have ample experience, this hands on approach can take longer than planned, which may cost more.

Simon’s involvement was originally only going to extend to stick-building the timber frame on site, but after all the delays getting out of the ground, he employed a company to prefabricate a frame and crane it up in sections from below.

“Materials are very important to me,” says Simon, “and timber is what I’m familiar with.” His attention to detail can be seen throughout, in the curved glulam beams, for example, or the cedar soffits, which have a shadow groove cut into them.

“I’m so glad I spent two days putting those in,” says Simon. “People love it, and it gives the home some extra character.”

The same is true for the traditional wet-laid ‘scantle’ roof slate on the upper storey of the building. Each course diminishes as it rises, so that the slates are just two inches at the top, a roofing style that is local to Devon and Cornwall.

Stone is also the dominant material in the extensive hard landscaping throughout the plot, and most of this came from the site itself.

“I love stonework,” says Simon. “It couldn’t be more natural. It just looks right, because it’s from the site. I employed a very skilled guy to do this element. Materials were also reused after the chalet was demolished, such as the timber underneath the cedar decking.”

Green roof and underfloor heating

Practicality may be Simon’s stated aim, but the new home has a few eco-credentials too, most notably the green roof. Highly visible from the parking area above (and neighbouring houses), this was provided by a specialist company.

As Simon explains, it was more of an aesthetic choice than a desire to be eco-friendly: “It’s lovely to look at the pink and blue flowers, and the scarlet foliage, and it’s nice to attract birds and butterflies. But am I an eco-warrior? No.”

It was the same practical-mindedness that made Simon over-specify the building’s insulation. The walls each have 160mm of Rockwool, the roof 250mm of Celotex, and the floor has 200mm of the same material, with 55mm of thermal screed over the underfloor heating (run off mains gas) that warms the slate floors beautifully.

Their first quarterly heating bill was minimal, even though Simon decided against specifying any renewable technologies.

“I dislike solar with a passion. It destroys the balance of a house aesthetically, and I don’t believe that the government’s system for paying for what you generate is very fair. I feel the same about air source heat pumps, and I think they can be both noisy and unsightly,” says Simon.

“However, one modern technology that I really do like is underfloor heating. I was very sceptical of this at first, but I’m amazed. It’s very efficient. The lack of radiators also helps to emphasise the home’s streamlined interiors.

“I really enjoyed working on the internal layout; moving things around and getting another two inches out of a room where possible. I also enjoyed including useful features; such as shoe racks and storage for outdoor clothes, and sourcing the innovative bathroom tiles that conceal light switches, activated at a touch.”

Simon also customised the cream gloss Ikea kitchen, forgoing cupboards for drawers. “You get three times the volume in a drawer; more space for your buck,” he says.

He also chose Corian for the worktops and has been hugely impressed with both the performance of the material itself and the company that installed it, Unicom, which even left him with a ‘chopping block’ and resins in his chosen colour, should a repair ever be necessary.

Landscaping and completing the build

Due to the gradient on which the house was built, landscaping considerations came into play even before the property was finished.

“The hard landscaping is as much a part of our home as the structure itself,” says Simon. Nevertheless, the 82 steps down from the parking area to the front door were one of the last things to be finished.

“It’s worth the trek, however, when you stand on the infinity deck. There is nothing in sight but the Atlantic swell rolling in and crashing on the rocks below,” he says.

This was a very personal project by someone who’s spent most of his life in the building industry. “The house will be our last home, as I plan to retire on this high note,” says Simon. “Architecture should give you a reaction, and this must be the most photographed building in Fowey.”

Published: April 2013

Login/register to save Article for later

Login/register to save Article for later