House Design Masterclass Part 3: Initial Concept Design

Once you’ve found a building plot and appointed an architect, it’s time to start designing your house. This is when the real fun starts.

After all the hard work to get to this point – not to mention the money spent on the land – you’ll probably be keen to get cracking and submit a planning application. However, it’s worth spending a little time on this stage and relishing the chance to experiment with ideas.

For a few weeks, you and your designer will be able to concentrate on the drawings and investigate possibilities without outside interference. Once your submission is in front of the planners, other people will begin having their say and you’ll have to persuade, cajole and negotiate with them to protect your concept.

PART 2: SITE SURVEY AND ASSESSMENT

Work out a build programme and try to stick to it by all means, but make sure there is plenty of time built in for creative experimentation. Developing a scheme is challenging and involves intensive discussions between you and your designer, but it should still be a period to enjoy yourself and embrace creativity.

In these first stages, you can afford to cut your architect a bit of slack, as you may have only met each other a couple of times. Saying that, you do need to build an effective working relationship as quickly as possible, as they need to be able to tune into your way of working, spot any burning issues and pet hates and identify decisions you are happy to delegate.

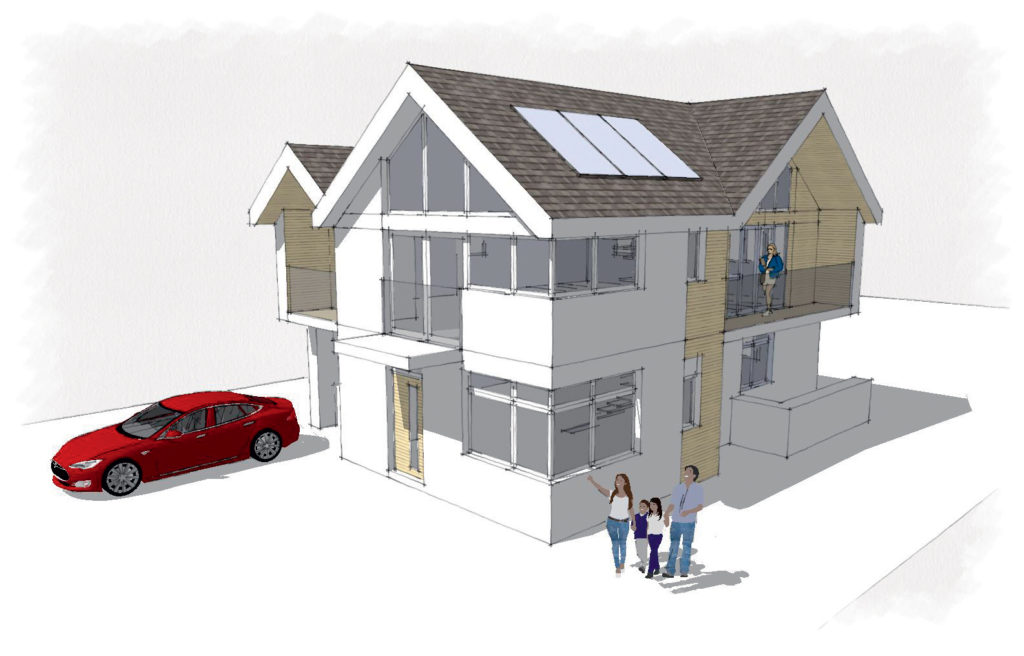

A lot of architects will make a 3D model of a scheme prior to confirming a design. You can also have a go at creating one yourself by using a Lego model house building kit

These early discussions will be easier if you have done your homework before the first line is drawn, so you are ready to answer all of the predictable preliminary questions that are likely to arise. To avoid sending your designer up too many blind alleys, there’s plenty of information you can pull together so the creative process can begin.

Before you purchased your plot, you should have worked out your self build budget in detail and so be able to estimate how much you can spend on construction. You should also be able to identify any architectural features that might inspire the design.

Our free cost calculator will help you make a budget, if you haven’t already.

Creating a brief

The other essential ingredient is your initial brief. This usually divides into ‘right brain’ practical matters and ‘left brain’ inspirational ideas. Your functional requirements are likely to include the number of rooms you want, their sizes and how they will be used.

You can probably list a great deal about your current needs, but don’t forget that the way you use the house will change over time, especially if you live in it for many years.

If you expect to grow old there, or have friends or relatives with impaired movement, you might want to include wheelchair-friendly access, or space for a stairlift or elevator to be added in the future.

Architects Millar + Howard Workshop won over the Locke family with their ability to undertake their dream complex design

Getting your personal tastes across can be a challenge if you rely on listing or discussing them. The old cliche that a picture says a thousand words is apt here; a scrapbook of photos and drawings can give a very good idea of your preferences. You don’t need to find an exact illustration, but any visual clues you can provide will be helpful.

Sorting through magazines, websites and photos of beautiful properties can be fun, but it’s just as important to include a few buildings or details you hate. The aim should be to create a visual guide for your architect or designer to follow as a scrapbook or digital file.

Need more advice about different aspects of your project?Build It’s Self Build Virtual Training will give you the detailed know-how to successfully realise your dream home. Our interactive courses are presented by Build It’s expert contributors and designed to give you the key nuggets of knowledge you need – all from the comfort of your own home. Covering everything from finding land to planning permission and design, our courses take place online and allow for audience participation and experience sharing. Use the code TWENTY for 20% off. |

It can be updated regularly to provide inspiration for the sketch right through to helping you choose ironmongery and wall tiles. Of course, there may be more than one person choosing pictures and if you don’t agree, it’s best to resolve any differences prior to handing over your final brief.

Communicating clearly

The planning officer is going to be a member of your architectural team whether you like it or not and, if you’re really unlucky, the planning committee might get in on the act as well. As such, it makes sense to research the influence they might have on your scheme before

it becomes fully fleshed out.

You’ll get some hints by looking at the planning department’s section of your local authority’s website, which will have examples of houses that have been approved in the past. Usually, each application includes a summary of the officer’s report, which should provide clues as to how your preferred style is likely to be received by them.

In order to ensure their bungalow renovation and extension gained planning permission, the Fernandez family invited the local planning officer over to visit to discuss the plans

Collaborating with an architect on a concept can be a delicate process at the beginning. To get the most out of your professional, you need to give them free rein to try out ideas and accept that they may not get it right first time.

No architect worth their salt will take the information you have assembled, come back with a fully resolved plan and expect you to approve it. If this happens, then you are probably working with the wrong person.

Find a credible architect for your project.

On the flip side, if you have very fixed ideas that you do not want to change, you may not need a designer and trying to work with one could turn out to be a painful experience for both of you.

Developing an individual house is an iterative process involving the free exchange of ideas that are conceived, illustrated, discussed and then revised. This might happen many times and both parties need to accept that there may be failures along the way before a concept is agreed.

Often, an apparent setback turns out to be an essential step on the way to achieving something wonderful. Most creative people can tell you of times they tried to refine an idea that appeared to be failing only to stop, reappraise and try something different, which turned out to be a solution.

Generating Ideas with your Architect

|

Time spent investigating a concept, even if it seems unfruitful, is never wasted. As you generate and test ideas, learn what works for you and where you are prepared to compromise. A frank exchange of ideas is essential to the success of the whole project.

You must be able to criticise the architect’s suggestions openly and explain why you think they are not working. Professional designers are well used to being questioned and even disparaged; that is something which comes with the territory.

Thinking outside the box

If you’re working with the right person, they’ll be ready to justify their strategy without taking offence and consider your point of view if they fail to persuade you.

Conversely, if an architect suggests something that strongly contradicts your own vision, don’t immediately dismiss it out of hand. Sometimes lateral thinking, or even an apparently stupid idea, is the first step towards creating something great.

This is a typical architect’s sketch of a scheme in the preliminary stages. This is an early drawing of Build It’s Education House, created by Opinder Liddar from Lapd Architects

One quote that I like is attributed to the car magnate Henry Ford: “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.” He was not implying that his customers’ needs should be ignored, just that the best way to meet them may not be immediately obvious.

This concept phase can be stressful for the designer. It is rare for an excellent idea to materialise without spending a significant time mulling over different solutions.

The tutor training well-known architect Sir Norman Foster first realised his potential when he saw all the discarded ideas piled up in the wastepaper bin next to his drawing board. At this stage, you are dealing with nothing more than marks on paper, which can be easily rejected or refined.

It is much harder and more expensive to change your mind later on. Even if building work hasn’t started, you may have to pay for a redesign and new planning application.

So, once you settle on a scheme, you need to be confident that it is the best possible solution because you have investigated the alternatives and know they aren’t as good.

Login/register to save Article for later

Login/register to save Article for later