21st-22nd February 2026 - time to get your dream home started!

BOOK HERE

21st-22nd February 2026 - time to get your dream home started!

BOOK HEREAlthough there is a great deal of current debate about Building Regulations not changing fast enough to keep up with modern efficiency demands, the rules regarding external wall insulation are an exception.

Gone are the days of simply picking an outer brick and an inner block and adding in some arbitrary cavity insulation; today, the process is a fine (and very calculated) art.

Having two layers of brickwork with a space between them is known as cavity wall construction. This method was first introduced in the early 20th century as a way to provide better protection against penetrative damp and to help keep the inside of walls dry.

Dense concrete blocks started to be used for inner cavity layers after the Second World War, with lighter weight blocks (with air insulation) introduced in the 1960s and 1970s. A decade later and insulation started to be introduced into the cavities.

The significance of airtightnessExternal walls make an important contribution to airtightness, which is key to overall energy performance. It’s all very well spending time and effort selecting products, but if the interface and detailing is poor then the house could suffer from heat escaping. The Building Regs set an air leakage limit of 10m3/hm2 at a regulated pressure of 50 Pascals – but in practice you’ll probably need to achieve at least 5.0m3/hm2, which is effectively five air changes per hour under testing. By comparison, a property meeting Passivhaus standard would have to achieve 0.6m3/hm2. |

Today, thermal (air-concrete) blocks are made from pulverised fuel ash (PFA) and sand, plus a cementitious binder (lime/cement) and raising agent, which allows the mix to rise in its mould.

They are lightweight and easy-to-handle, plus there’s minimal conductivity (which makes them relatively good insulators). Different thicknesses and strengths can be produced.

Increasing strength usually also ups the density, which reduces conductivity (so it’s less insulating, but offers better thermal mass). Good performance can be achieved with

all these blocks; it’s about choosing the right overall wall makeup.

Achieving the threshold U-value of 0.30 W/m2K is straightforward. Most big developers would do this with 300mm-thick walls, consisting of a 100mm external facing brick, a 100mm internal thermal block and a choice of insulations in the cavity gap.

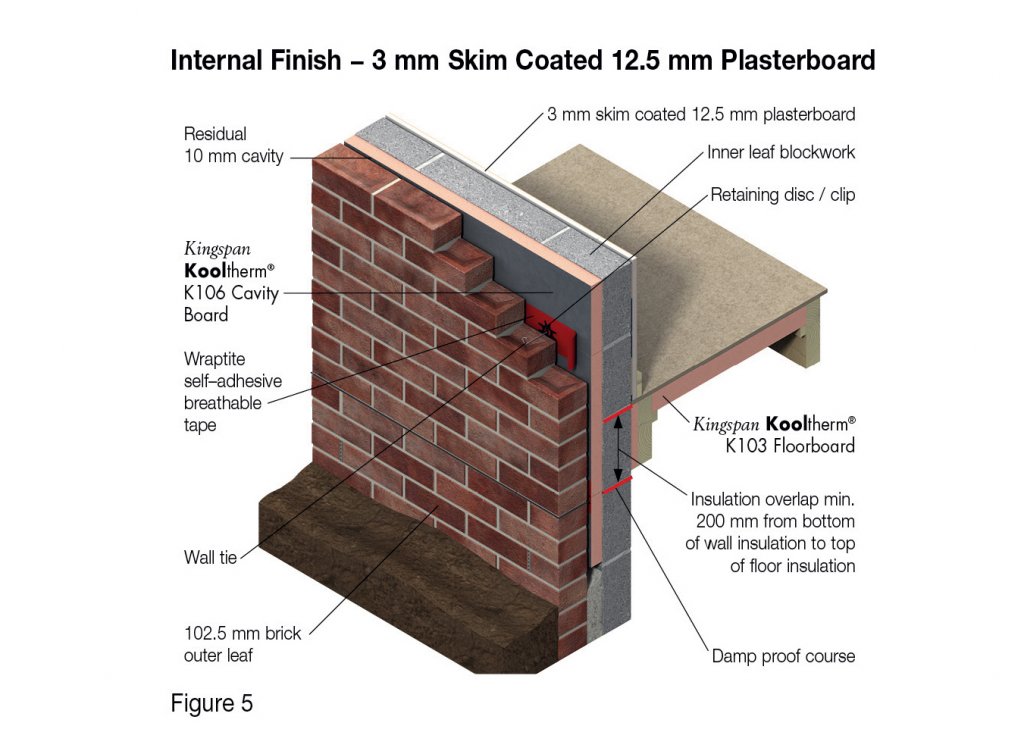

This diagram by Kingspan shows how the Kooltherm K108 Cavity Board fits into the external wall system, needing only a 10mm gap

Source it: Find Kingspan Insulation products in the Build It Directory

This sits comfortably on a 600mm foundation (with 150mm safety margin on either side). In practice, you’ll want better U-values, which means you’ll need to increase the insulation thickness and/or opt for a more substantial internal block skin. Alternatively, using a specialist insulation known as Cavity Therm will allow you to keep a 300mm wall thickness.

Blocks are bought from builder’s merchants and each retailer generally has their own favourite supplier. Shop around until you get the product you want from the trader that has the best supply arrangements – 100mm-thick lightweight blocks bought in a bulk order are likely to cost in the region of £15-£20 per m2.

A neat way to improve performance is to go for thin-joint. The blocks used are basically the same (albeit larger).

The main difference is that a thin layer of adhesive grout is used to bond the units together instead of the standard 10mm mortar bed. Normally, the sand and cement mortar paste makes up roughly 7.5% of the wall; and as it’s a highly conductive material, it reduces thermal efficiency.

By comparison, the thin joint option makes up closer to 1% of the wall face, meaning a more insulated and airtight system.

Insulation jargon busterYou’ll need to understand the following terms to make sense of the insulation options for your new building. If in doubt, leave it to your architect or professional advisers as the end composition must both pass the TFEE/DFEE and TER/DER tests under SAP.

|

Porotherm blocks might suit any self-builders keen on a more natural product. Made from clay, the hollow core of these units mean they can be used as either inner or outer skins; alternatively, they can form a single, monolithic solid wall.

While these units’ credentials may be more ecological, Porotherm blocks are more conductive than concrete units (with a K-value of 0.29 W/mK in comparison to 0.11 W/mK).

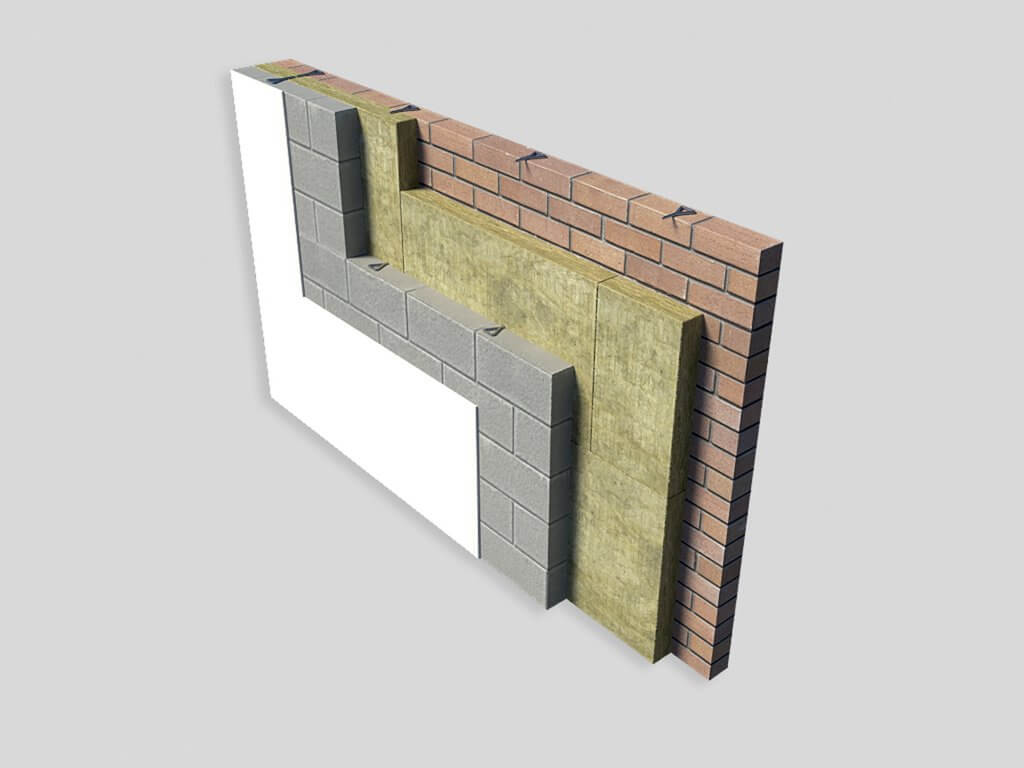

The main choices are large rigid-foam PIR (polyisocyanurate) boards; EPS (expanded polystyrene) sheets; or mineral wool – the generic term for rolls or semi-rigid batts of fibreglass or rockwool. EPS and mineral wool have similar K-values, whereas PIR is significantly better.

Insulation can be added to the wall cavity in two ways. One option is to partially fill the gap, leaving at least 50mm clear. Kingspan has developed a product (K108) that reduces the retained gap to 10mm.

The other route is to fully fill the void; however, this isn’t recommended for very exposed locations (on the coast, for example) and any facing brickwork wouldn’t be allowed to have recessed mortar joints, which could affect your choice of external finish.

You can fully fill the cavity with a mineral wool product or with PIR Cavity Therm, which has a 5mm factory-installed plastic protective outer layer. Generally, however, PIR isn’t allowed as a full-fill option because it could react with the outer skin’s damp mortar.

Insulating a single skin external wallYou could use a thicker single block to form your new home’s walls, with insulation added either internally or externally. This method is a clever way of reducing the overall wall thickness, meaning you may be able to reduce the foundation width to 450mm. With house values largely calculated on gross internal areas (GIA), keeping your walls thinner could increase floor space and profit. However, departing from the protective characteristics of the cavity wall could risk interstitial condensation (IC), so seek specialist advice to gauge the risk, as this will be affected by the mix and arrangement of building materials selected. Generally, this type of system will have a rendered external finish. To achieve a U-value of 0.18 W/m2K, you could use 80mm PIR in conjunction with a 215mm thick super light block. Deciding whether to put the insulation on the inside or outside of the system could come down to whether you want directly applied plaster on the inside. Even plastered lightweight blocks will be able to soak up and release some heat. |

Let’s assume you want to achieve the Building Regs notional dwelling U-value target of 0.18 W/m2K. You could achieve this within a 300mm build-up with 100mm lightweight blocks and 100mm of Cavity Therm insulation.

Alternatively, you could increase the overall wall thickness to 350mm and use 100mm PIR in the gap with a 50mm cavity between the insulation and brickwork. This option also works with no cavity gap by using 150mm mineral wool as a full fill between the block and brick.

In terms of cost comparison, 100mm thick PIR comes in around £15 per m², whereas 150mm of semi rigid mineral wool insulation would cost £9 per m².

Quick tip:The latest Building Regulations governing thermal performance in external walls are set out in the government’s Approved Document (AD) L1A – Conservation of fuel and power in new dwellings. |

Another option is to add insulation to the inside face of the blockwork by opting for laminated plasterboard. With this product, varying thicknesses of PIR insulation can be glued to the boards in the factory to achieve the spec you want.

The result will be a dry-lined internal finish, secured to the walls with wet plaster dabs and then skimmed or taped and jointed as required.

This technique means the 300mm core wall can be retained, with a 100mm full or partially filled cavity, plus the laminated plasterboard hanging on the inside of the block skin. So it will increase the overall wall thickness, but won’t change the bearing on the foundations.

There are also opportunities to introduce conduits for services with this method, which would make them easier to install later on.

Top image: Kingspan Kooltherm K108 Cavity Board is a high performance insulation option with a composite foil facing; it’s used in partially filled cavities