Retrofitting Insulation – How Can You Upgrade an Existing Home’s Insulation?

Retrofitting insulation is one of the best ways to help reduce your home’s heat loss and reduce your energy consumption over time – but how should you go about adding insulation to your home? Deciding whether and how to upgrade the insulation in your existing home isn’t straightforward. Much depends on what (if any) insulation is already there, as well as on the thermal and moisture properties of the existing thermal envelope.

The condition of the building fabric and type of building you’re working with is critical, too: a dry wall is much more thermally effective than a wet one. If you have an older, period house of traditional construction, it’s likely to have some heritage value, which must be accounted for in the decision-making process.

Here, two of Build It’s experts, Nigel Griffiths and Alan Tierney, take a look at the best ways to retrofit insulation as part of a renovation project, and how to make effective upgrades to a period home.

What Do You Need to Know Before Retrofitting Insulation?

Build It’s eco expert, Nigel Griffiths, takes a look at how to develop an effective retrofit strategy when upgrading your home’s insulation to ensure an efficient property.

|

Nigel GriffithsNigel Griffiths specialises in sustainable construction and eco-renovation and is the author of the Haynes Eco House Manual. He advises UK government on retrofit programmes and inspects renewable heat installations on behalf of Ofgem. |

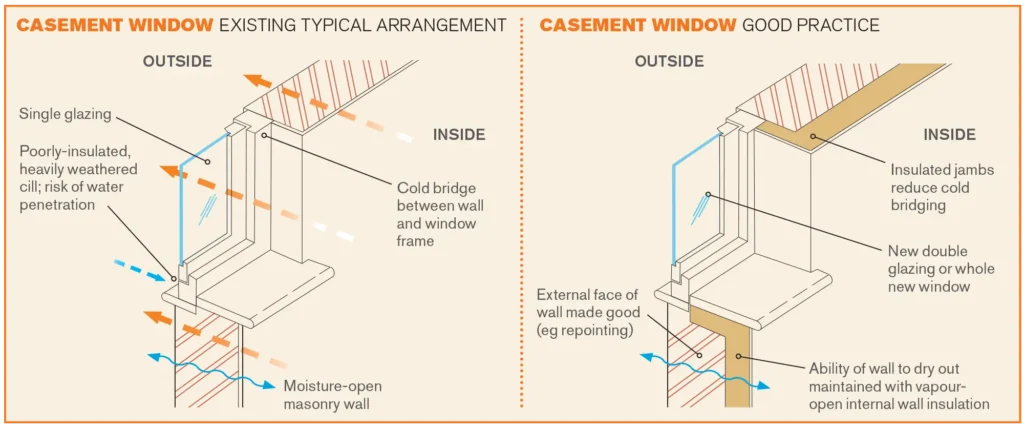

Individual thermal elements, such as a building’s windows, walls, floors and roof, cannot always be treated independently. These elements have junctions with each other, and by insulating one thermal element you make another relatively cooler. This can lead to condensation and mould growth where there was none before – so, sometimes the adjacent building fabric will also need to be addressed.

A retrofit strategy must also go beyond insulation. The lead technical author of the Publicly Available Specification on retrofit (PAS 2035) has a saying, adapted from protests made ahead of the US Declaration of Independence: “no insulation without ventilation!” The process of improving the thermal performance of walls, roofs windows etc reduces natural ventilation (air leakage).

Many houses rely on this to provide adequate fresh air to breathe. So, it’s essential to investigate this whenever you’re retrofitting insulation, and to improve ventilation wherever necessary.

Natural products, such as as Thermafleece sheeps wool insulation can deliver excellent thermal efficiency whilst also helping to maintain a healthy home

In addition, you won’t get the full benefit of improving building fabric performance when retrofitting insulation unless your heating system can respond accordingly and reduce your energy demand.

At a minimum this would mean installing thermostatic valves (TRVs) on each radiator – so they switch off once the relevant room is up to temperature – and a timer control and thermostat for the whole system. The advent of wireless technology means that highly sophisticated smart control systems such as smart thermostats can be retrofitted with minimal disruption.

Which Insulation Materials Are Best for a Retrofit?

Once you’ve decided to upgrade the performance of a wall, door, window, roof or floor, it’s important to think about the materials that will be used. Saving money on heating bills will of course be a big factor in your retrofit, and it’s relatively straightforward to do some cost-benefit analysis there.

If you’re also driven by concerns over climate change, then it would be pointless to do work that causes more CO2 emissions than it saves over the life of the measure. You’ll therefore want to consider the embodied energy not only of the insulation products, but all the materials going into your project and the impact of fitting them.

Retrofitting insulation strategies & risks

In all cases, don’t forget to check that adequate fresh air is provided in all rooms, adjust your heating controls, and address junctions with adjacent thermal elements to prevent thermal bridging. |

Generally, the less processed and more sustainable an insulation material is, the lower its embodied energy and carbon. For windows, the optimal sustainable option would be timber, as this not only has a low embodied carbon, but also locks up CO2 for the life of the product (this is known as sequestered carbon).

At the other end of the spectrum, plastic window frames are difficult or impossible to recycle. Good quality timber fenestration can last much longer than plastic. What’s more, paint technologies have improved hugely, resulting in much longer intervals between maintenance.

Mike Wye provided the Steico woodfibre insulation for this retrofit project. The vapour-permeable material is produced using wood from sustainably managed forests

The same logic holds when specifying insulation products. Polyisocyanurate and polystyrene are high-performance, but they’re made from oil (ie plastics). There are plenty of lower carbon materials available. Mineral wool is an excellent choice, as it’s inert and produced from a plentiful resource. But if you are working with a traditional (solid walled) building, then there are good reasons to use more natural materials, such as wood wool.

TOP TIPS What to do before you begin retrofitting insulation

|

Natural insulations are vapour-open. So, they’ll be consistent with the underlying brick or stonework, which will have been constructed using breathable lime mortar rather than cement. They also have moisture-bearing capacities, so they can buffer some of the changes you get within the internal environment due to variations in occupation and use. Hence using natural insulation results in a better internal air quality.

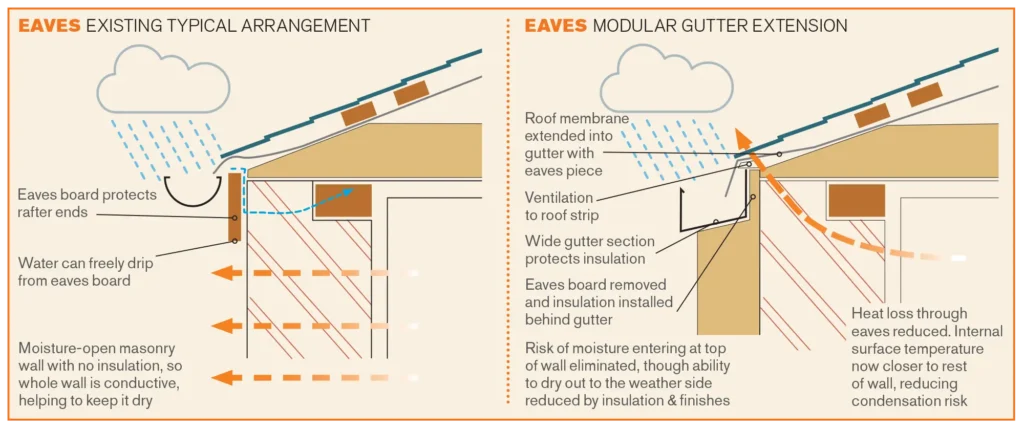

In some circumstances, it’s essential to use high-performance products when retrofitting insulation to minimise thermal bridging. For example, lofts are frequently insulated or upgraded with mineral wool – but at the eaves, there’s often a junction between the wall and pitched roof where mineral wool insulation cannot be fitted. In this case, a higher-performing board can instead be inserted between the rafters (taking care to leave a gap above for ventilation).

Similarly, if you have insulated a wall internally, then you have the problem of terminating the insulation at the window and door reveals. The thickness of material you can fit is limited by the depth of the outer frames. A high performing board (such as an aerogel mix) would be the most effective way to reduce the thermal bridge at this point whilst still leaving some of the frame visible.

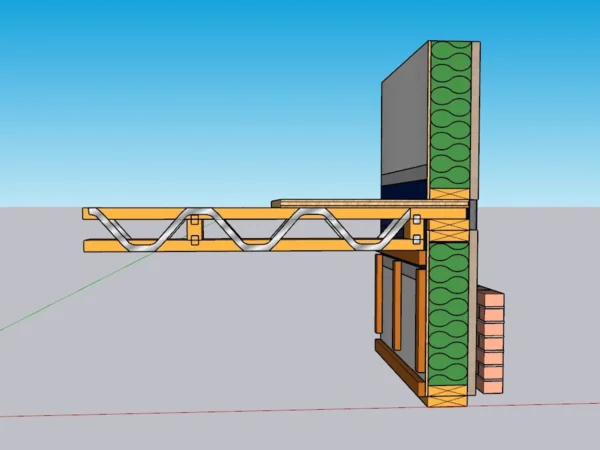

This diagram shows the ways a home’s window and surrounding structure can be insulated. Original illustrations by Robert Prewitt

How Much Insulation Should You Use?

When deciding the amount of insulation to install, one approach is to consider the limiting U-values set out in Building Regulations Part L1B. A U-value represents the rate at which heat is conducted through a given building fabric element – such as a wall, roof, window etc. When renovating a fairly typical house, some people will just default to the maximum allowable U-value and design accordingly. However, this isn’t likely to deliver optimal results.

For instance, if you’re applying external insulation to a wall, it will often make sense to exceed the standards set out in the Building Regs. All the other costs of the work – access, finishes, moving services etc – will stay the same no matter how much thermal material you add. So, the extra cost of upgrading to thicker insulation will be relatively low and is likely to prove a good use of your building budget.

Conversely, when it comes to lofts, the current recommendation is to use 300mm of mineral wool. However, if you’ve already got 150mm of insulation, the cost and embodied energy of topping this up may not deliver significant savings in practice.

This diagram shows the different ways the eaves of a home can be insulated. Original illustrations by Robert Prewitt

The same principle applies to window replacement – the difference in U-value between double glazing (around 1.4 W/m2K) and triple glazing (approx 0.8 W/m²K) is unlikely to repay you in terms of energy saved versus the additional financial and environmental cost this upgrade would impose.

Some homeowners will aim for higher performance targets when retrofitting insulation, such as the EnerPHit Passivhaus model for retrofits. Such standards can be quite demanding, and it’s always worth weighing up the pros, cons and costs before proceeding. You may be able to deliver the quality of living space you want without going the whole hog.

Retrofitting Insulation While Renovating a Period Property

Build It’s period property expert, Alan Tierney, explains why it’s important to understand the building fabric of a period home before taking steps to improve its thermal performance.

|

Alan TierneyAlan is a period property and conservation specialist. He ran a historic building consultancy, offering hands-on advice to the owners of heritage homes, but is now focused on renovating Old Barnstaple House. |

Your home is likely to fall into one of three general groups – and it’s important to bear in mind that the appropriate insulation solution for each is quite different. The first category is old, traditionally constructed houses built before 1918. The second bracket encompasses mid-20th century properties, erected roughly between 1919 and the 1990s. The final type is for modern dwellings.

Old, traditionally constructed houses were developed with no conscious efforts at insulation. That being said, many of the construction methods and materials used were inherently thermally efficient, such as thatched roofs and thick walls incorporating earth, as well as clay-and lime-based binders and renders. They also tend to benefit from high thermal mass, which helps to retain warmth.

In these houses, damp and airtightness are often much more prevalent issues. It’s vital to understand that these buildings were constructed from permeable, absorbent materials with no vapour barriers or damp proof course. For them to work effectively and – most importantly – stay dry, any insulation materials incorporated into the fabric must be vapour permeable and hygroscopic. In practice, that means using minimally processed natural fibre insulation. Appropriate solutions include wood fibre, hemp, sheep’s wool and recycled newspaper.

CASE STUDY Victorian house with upgraded insulationAs part of the renovation and extension of the ground floor of this Victorian property, Whittaker Parsons developed a strategy to improve its thermal performance. Insulation made from recycled coffee bean bags was fitted in the existing ground-floor structure, laid above an airtight membrane to prevent heat escaping. Gutex Thermoflex woodfibre insulation was installed in the walls. Photo: Jim Stephenson |

Mid-20th century houses are often found to offer the worst performance in terms of heat loss. They were built using modern materials, largely cement and hard fired bricks, with uninsulated cavity walls. They have limited thermal mass, so the fabric tends to cool quickly. For much of this period, oil was cheap and plentiful and the dangers of climate change weren’t generally recognised. As a result, minimising a house’s heating requirements during construction wasn’t considered a priority.

Modern dwellings have been subject to increasingly stringent regulations for conserving heat and power. For example, they must incorporate a protective thermal layer in the walls, floors and roof. Cavity walls will be insulated and incorporate a physical vapour barrier that prevents water penetration from bridging the gap via the insulation.

If there are issues with this, the best course of action will likely involve upgrading the fabric to conform with more recent regulations, or by rectifying any failures made during construction. Unfortunately, poor standards, inadequate enforcement of the standards and the use of low-quality materials to minimise costs have always been common, particularly in volume housebuilding.

Where Should You Prioritise Insulation?

It’s important to know where around the home you should be insulating to ensure maximum return on your investment.

Retrofitting roof insulation

Loft insulation is the cheapest, easiest and most effective means of reducing heat loss from your home. For buildings constructed before 1918, the product you specify should be in the form of quilts or batts of insulating fibres. These can be simply rolled out over the ceiling below. For more modern homes there’s a range of alternative solutions including rockwool, recycled PET (polyethylene terephthalate plastic) or fibreglass – but be aware that this is hazardous, so protective equipment must be worn during the installation process.

Rockwool stone wool insulation is made from naturally occurring basalt volcanic rock, mixed with recycled and upcycled secondary materials. It can be used to treat walls, floors, ceilings, roofs, pipes and ducts

Current regulations stipulate a minimum insulation depth of 270mm. Old buildings will originally have had no protective thermal barrier in the attic at all, and even modern properties that pre-date 2003 are unlikely to have a sufficiently thick layer. It’s also essential that cross ventilation of the roof space is maintained – the insulation material you choose should not extend right up to the eaves, where there should be open vents to the outside.

Warm roofs, where the insulation is above the roof space, are much harder to deal with – any upgrades you make are likely to require the services of a specialist contractor. However, it’s still important to ensure loft insulation is sufficient and should be your top priority to yield the best return on your efforts.

Retrofitting floor insulation

In addition to contributing to a property’s overall levels of heat loss, uninsulated floors have a disproportionate effect on the comfort of occupants, due to the fact that you’re, more or less, always in constant contact with the floor.

Modern buildings almost exclusively have insulated solid floors and shouldn’t need any attention. Older buildings might have either solid or suspended timber floors, the latter of which will not originally have been insulated. This type of structure also tends to be draughty, so both issues can be resolved at the same time.

Insulating a suspended timber floor should be relatively straightforward and affordable. The most difficult task is lifting the floorboards carefully so they can be replaced afterwards. This might require a seasoned carpenter – the older the floor, the more skill is required and avoiding damage becomes more important.

PYC Insulation was appointed to install Warmcel insulation, made from recycled newspaper, in this house. The insulation is blown into the structure via an injection hole using a specialist blowing machine. Once the process is complete, the gap behind the injection point is fully filled and an airtight patch is applied

Once the boards have been lifted an airtightness membrane can be draped and stapled to the joists to form pockets in the spaces between. These compartments can then be filled with insulating material; loose fill cellulose works best and is relatively low cost. The boards are then simply replaced.

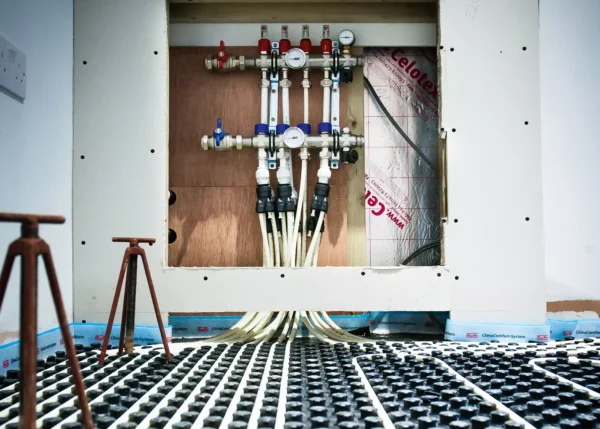

Solid floors present a greater challenge. If there are high ceilings it may be possible to insulate over the existing floor and lay a new finish on top. However, this is likely to cause difficulties with dimensions across the ground floor, particularly in doorways, which can be costly to resolve.

Usually, the only solution is to dig out the floor to a sufficient depth to incorporate the insulation material, a new floor slab and finish. This is expensive, highly disruptive and is usually only justifiable if there are also damp issues associated with the existing floor.

In older buildings with shallow foundations, extreme caution is required. It’s also worth bearing in mind that this intervention wouldn’t be appropriate if it would lead to the loss of a historic floor of any value.

Retrofitting insulation in the walls

Heat loss through walls is dependent on the nature of the partition. Uninsulated cavity walls or single skin brickwork are the most problematic. Thick solid structures, on the other hand, should perform better and benefit from considerable thermal mass.

Retrofitting cavity wall insulation has long been a standard solution; it can yield significant benefits for a limited cost, with minimal disruption. But it’s not without risk. The space in the middle is intended to provide the barrier to penetrating damp; there is no physical vapour barrier as in a modern cavity wall.

CASE STUDY Listed building with upgraded wall insulationIan Hazard Architects developed the plans for the renovation and conversion of a listed cart shed in North Yorkshire. As a building of solid stone construction, the use of modern plastic or non-breathable materials was not possible. Instead, the external stone walls were repointed with non-hydraulic quick lime mortar. Once the walls had been repaired and dried out, they were insulated internally using a natural, breathable wood fibre solution, before being finished with a coat of non-hydraulic quick lime plaster. Photo: Scott Wicking |

Filling the aperture with insulation material can bridge the gap, enabling damp to penetrate to the inside. The risk is minimal for sheltered buildings but increases dramatically with the degree of exposure. Retrofitted buildings in high exposure zones (mostly the west of Britain) have suffered serious consequences that are difficult to resolve.

Internal wall insulation can be a good solution for these structures if there’s sufficient internal space to accommodate it. Alternatively, external wall insulation is an option if it’s possible to make the necessary alterations to exterior design details such as eaves, rainwater goods and windowsills. Neither option is straightforward, and requires detailed specification by a specialist.

Insulating solid walls is more problematic and carries risks of damp, mould growth and fabric decay. I generally don’t recommend it. There are, however, instances where it is considered necessary. In these scenarios, the only material that’s been used successfully in heritage homes is wood fibre insulation board. It is essential that any specification is carried out by a highly qualified specialist.

Login/register to save Article for later

Login/register to save Article for later

Very good article. The risks with regard to retrofit insulation are significant and its great to see this issue put to the fore. Also great to see the comments over good quality timber windows/doors rather than UPVc. Keep up the good work. My question would be – “What is the objective with regard to retrofit insulation”? If the answer is to reduce the use of fossil fuels (FF) then the simple solution is the look at the heating system. If for example you use 100% green electricity and you have all electric heat, then you have reduced to use of FF to near zero, and this is far easier and less costly to acheive than retrofit insulation and removes the risks. If it is a cost saving and reduced FF then the same route but use battery storage (and Solar PV if you wish) to reduce the aquisition cost of the electricity. My personal view is that is a much better way to go.

Thanks again.