How to Insulate a Period House

The thermal performance of our homes is a matter of increasing importance for a number of reasons, in particular managing CO2 emissions, fuel costs, health and comfort.

For different people, living in different types of property, the ideal balance between these priorities will vary – but all will need to be considered when developing an effective strategy to make improvements.

Another factor that must be taken into account is the health and condition of the building itself. For a heritage home this element is of particular importance, partly because of the need to protect its inherent cultural value and character. But this is also due to the fact old buildings are complex environments, sensitive to changes that may have serious unintended consequences.

Building structure

Before undertaking any measures that will have an effect on the functional performance of a period house, it is essential to understand how the structure’s fabric works.

Homes built before about 1919 tend to be of traditional construction – so they feature solid walls that were generally made using soft, flexible and permeable materials.

They don’t incorporate vapour barriers or damp proof membranes (as with modern buildings). They instead manage damp and moisture in a different way, through absorption and evaporation. This is known as breathability.

The key rule is that any work you undertake to your period property must maintain the breathable performance of the building’s fabric.

Assess the whole house

It can be tempting to look at insulation as a stand-alone issue, often in response to an unfavourable energy assessment or a poor rating on an Energy Performance Certificate (EPC).

The causes of a building being cold, however, are much more extensive than those related to insulation alone. For a successful outcome, an overall whole-house approach must be taken. The first priority must be to ensure that the property is well maintained and free from damp.

Damp structures will lose significantly more heat than dry ones, in addition to presenting considerable risk to the health of both building and occupants.

See my article for an in-depth guide to dealing with condensation and damp issues.

Next on the list is airtightness – more heat is lost through draughts than through poor insulation, and this has a disproportionate effect on how cold we feel.

Any improvements in airtightness must go hand-in-hand with maintaining sufficient ventilation, particularly in wet zones such as kitchens and bathrooms.

This is vital to avoid excessive build up of water vapour, which will cause damp, condensation and mould growth.

Roof insulation

The most important element of a building to consider for insulation is the roof, as a very large proportion of heat lost from a house escapes here.

Fortunately, this is also the easiest place to treat in most homes, simply by laying insulation material on the floor of the loft (usually between and over the joists). However, if this is not done carefully, it can cause problems.

It’s important to maintain good ventilation of the roofspace above the insulation. To do this, there should be an open connection to outside at the eaves; the insulation material must therefore stop short of the eaves so as to avoid blocking this air gap.

The choice of insulation material is crucial, too. There are quite complex processes at work but, essentially, warm moist air rising through the building will tend to lose much of its water content as it cools.

Natural, hygroscopic insulation material is able to buffer this moisture while still maintaining its thermal resistance. Synthetic products cannot do this and, as a result, they tend to promote condensation in the cold roof space.

This represents a threat to the structural timbers and reduces the effectiveness of the insulation. Appropriate materials include sheepswool, hemp, woodfibre and sisal. Their insulation values vary, so you should always consult the supplier or a qualified expert to

advise on the appropriate thickness.

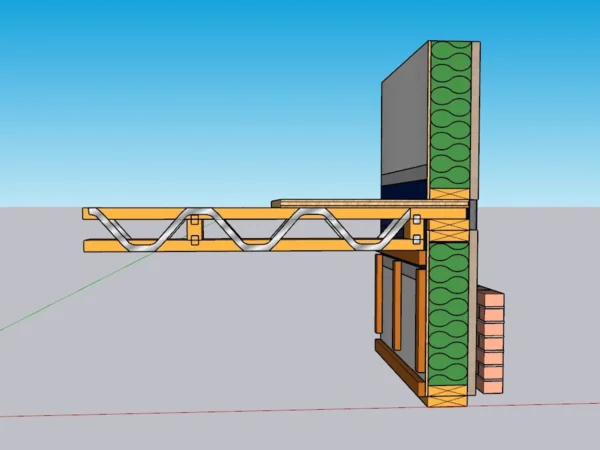

Some old houses have vaulted rooms (where part of the roof forms a sloping ceiling) or occupied attic spaces. In these cases, the whole of the roof area is being heated.

This scenario presents complex problems, where careful specification is required to maintain adequate ventilation and breathability. If this is not done successfully, serious decay of the roof timbers can result.

Woodfibre boards are usually the best material to go for, often in conjunction with sheepswool or a similar flexible, natural product.

Floor insulation

This is the element of the building with which you are most in contact, so adding insulation here can have a significant impact on comfort levels.

Suspended timber floor structures can often be carefully lifted without causing damage. It is then quite straightforward to drape a membrane between the joists and fill this space with insulation, before replacing the boards seamlessly to preserve the original character.

It is essential to use a breathable material to avoid causing damp and decay in the joists. Loose fill cellulose works well because it easily fills the voids without leaving any gaps. The ventilation space below the joists should be left unobstructed.

Top tips: Insulating a Period Home

|

Historic solid floors should not be disturbed so as to retain their character and value, meaning they don’t usually present any opportunity for adding insulation.

However, in many cases solid floors have been replaced over the years with uninsulated concrete versions. These can be removed and replaced with a breathable, insulated alternative comprising a base of foamed glass aggregate covered by a lime screed.

This is a specialist job that must be carefully specified. It is quite intrusive and disruptive but it can be worth doing, as it will make a considerable improvement to thermal performance, at the same time as greatly enhancing the building’s breathability.

If desired, underfloor heating can be incorporated into the new floor screed. This will provide an efficient, consistent, low temperature heat source that is good for both building and occupant health.

Wall insulation

Traditional buildings usually have solid walls, which means there’s no cavity to fill with thermal protection. EPCs therefore tend to rate solid walls poorly and often recommend insulation to improve them.

Unfortunately this assessment is usually not accurate, because the parameters used in the EPC are designed for modern buildings and do not apply to traditional solid walls.

Practical measurements of period properties show they usually perform much better than the assessments suggest. So in most cases, provided they are not damp, solid walls function adequately and the addition of insulation is not justified.

In some circumstances, for instance with very thin or particularly exposed walls, you will have to consider adding insulation. As this can fundamentally interfere with breathability, it carries very high risks for the building fabric and the health of the occupants – so it should only be specified and installed by a well-qualified expert.

A limited thickness of a breathable insulation material, such as woodfibre board, can be a successful treatment. Great care must be given to difficult details, such as window reveals, ceiling voids and wall junctions.

Finally, bear in mind that modern plasters are likely to interfere with breathability and moisture buffering within a period building.

This will adversely affect thermal performance. Stripping and re-plastering using suitable lime or clay plaster overcomes these problems and gives a major improvement in thermal comfort. Insulating plasters, incorporating cork or hemp, are available and will give some benefit with very low risk.

Top image: Architects Van Ellen & Sheryn renovated this farmhouse and rundown barn in Dartmoor.

Login/register to save Article for later

Login/register to save Article for later