Early Bird Offer! Free tickets to meet independent experts at this summer's Build It Live

Save £24 - Book Now!

Early Bird Offer! Free tickets to meet independent experts at this summer's Build It Live

Save £24 - Book Now!Older homes don’t have to be dark and dingy; they can be spacious and bright if they are renovated carefully.

How much light your property lets in will depend on whether it was designed with natural brightness in mind, when it was built, the construction materials used, its original function and if it has had alterations over the years.

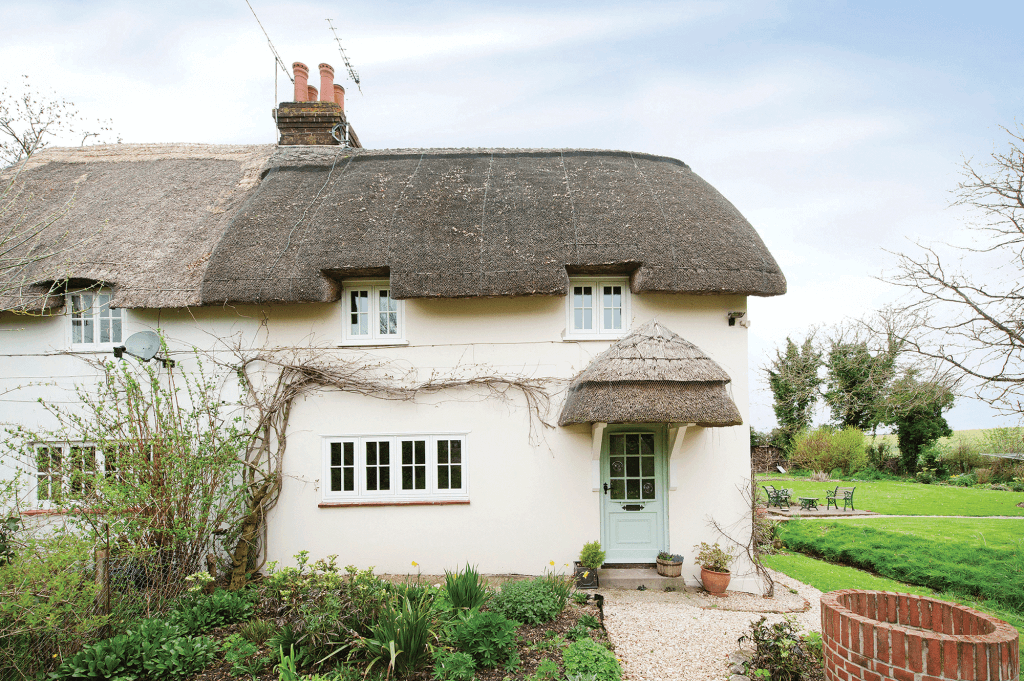

Medieval buildings are usually thought of as quite dark, with small windows. But higher status houses had open halls, which would have had very large, double-height windows; plus medium-sized openings in the parlour and much meaner apertures in service or storage rooms.

Improvements in glass making during the 17th century led to the development of larger sash windows. This made it easier to get daylight into homes but was quickly limited by the imposition of the window tax, which caused many openings to be bricked up to avoid the levy.

By the mid 19th century, the tax was gone. The Victorians were huge believers that daylight had important health benefits. This, along with technological advances, led to the almost universal use of large sash windows. These allow for significant amounts of brightness, but this does mean Victorian houses have more issues with heat loss through glazing than they do with letting in light.

The most straightforward and least disruptive method of getting more light into an old building is to identify former openings and reinstate them to create new windows. This is why it’s important to know a building’s historical background.

The better you understand the development of the house over time, the better your chance of identifying apertures that have been closed up in the past, when that was done and why.

Windows and doors will have been sealed up for various reasons over their history – done using a range of materials from historic bricks to breeze blocks. Reinstating an original opening will not disrupt the overall appearance of the building or interfere with the architectural intention.

In some circumstances it will be seen as a visual improvement, recreating the lost form. It is also probable that there will be no structural implication to creating an opening at that point. It’s essential to check this carefully to ensure that the structure was not altered at the time of closing up, or afterwards, and that it had been properly formed in the first place.

Demonstrating that a window has previously been bricked up does not necessarily mean it will be possible to reinstate it. If it was blocked in the 18th century to avoid the window tax, for example, it might be considered an important part of the history of the house.

A building of that age is very likely to be listed, so listed building consent would be required. If a window has not actually been bricked up but was originally built blind, there will be similar issues.

This means you’ll be creating a new opening but, at the very least, you can demonstrate the insertion is in the right place architecturally. You will have to do some investigation, as a blind window may not have been constructed as an opening with a lintel or brick arch to support it.

Houses with very thick mass walls, made of stone or cob, were built with very wide splays in order to maximise the amount of light getting through to the interior.

Later alterations, including the insertion of new windows to these openings, sometimes result in the squaring off of the window reveals, which greatly reduced the amount of light entering. Reinstating the splay, if possible, will result in significant improvement.

Inserting additional windows into old buildings can be difficult to achieve sensitively and without harming the character of the building. The most basic issue is that it will involve the removal of historic fabric that has an inherent value.

In all but the most sensitive situations, however, this should be possible to achieve in a limited fashion with careful planning. Usually, the loss of a small section of mass walling or infill can be justified, as long as the important details (mouldings, decorative features or sensitive historical elements like wattle and daub) are not harmed.

The next consideration is the effect on the structure. This does not just mean the provision of a lintel, but also the impact on load paths and the additional bearing on the remaining elements of the building.

However, the main difficulty with new openings is often their visual impact on the building – particularly if it is on the principal elevation. Windows and doors are often key elements of how a building looks.

This is particularly the case if there are designed elevations, or if the house is part of a group or a terrace. Alterations can have a considerable impact on the streetscape. If the building is listed or in a conservation area, listed building consent and/or planning permission will be required, and probably difficult to obtain.

An alternative to new openings in walls is to bring light into the upper storeys or double height spaces via rooflights. These are particularly good where there are hidden roof slopes, as installing the windows will have no notable visual impact.

Roof coverings have a limited service life, so there is no concern over the loss of historic fabric – provided the units can be located around any structural timbers.

These windows can even be successful on visible roof slopes, and are often preferred to creating new wall openings, particularly in buildings being converted to residential use. Low-profile conservation rooflights are usually most appropriate and careful thought needs to be given to their positioning.

This extension to a grade II listed old rectory by Witcher Crawford features cleverly placed roof windows, which allow light to flood into the heart of the home

All too often they are located solely to suit the internal layout without any consideration of how they will look from outside, leading to an unsightly mess.

It’s important that the layout is primarily driven by their impact on the external appearance, taking into account their number, spacing, alignment and relationship to other features such as eaves, ridges and hips.

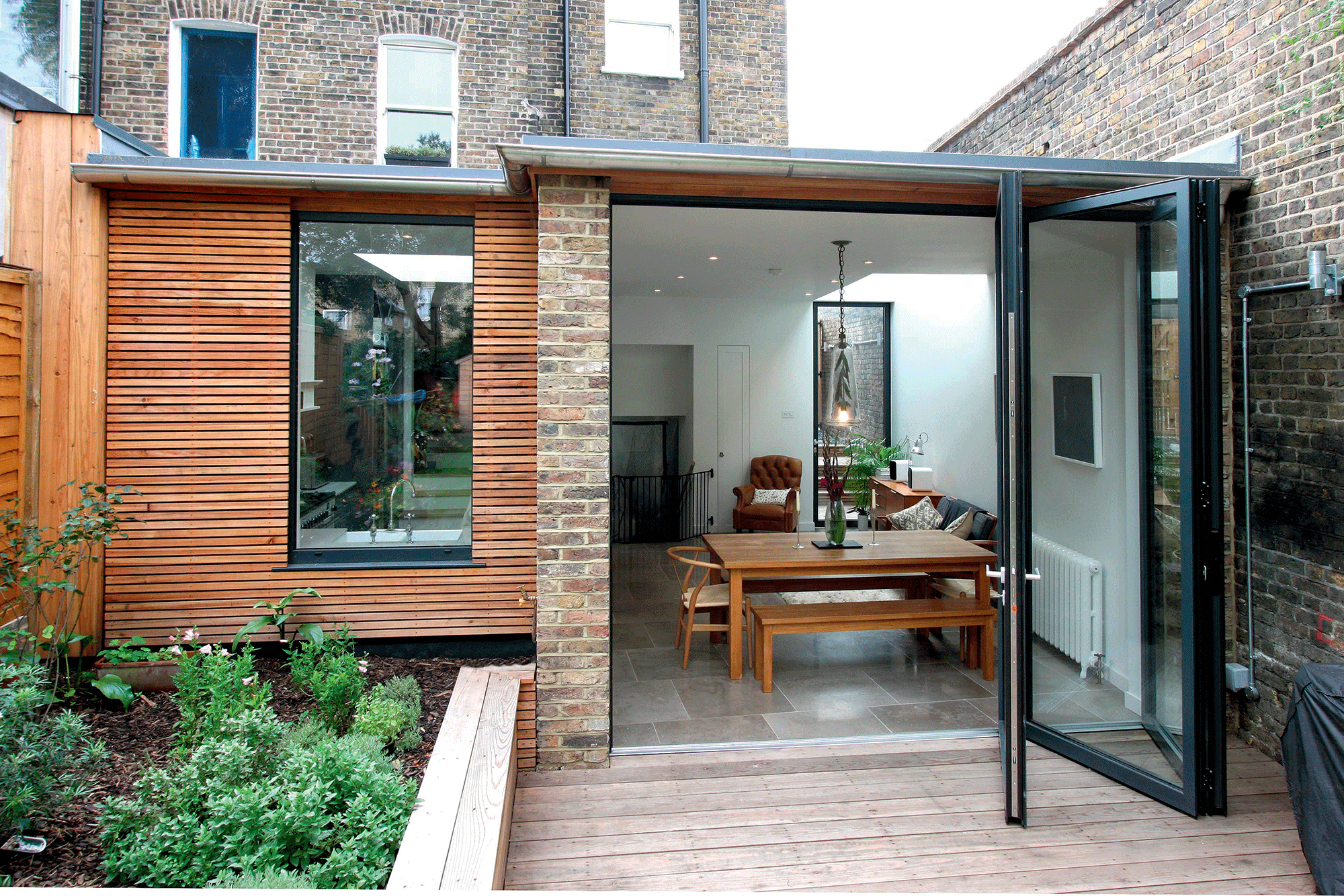

Strange as it may seem, adding a sensitively designed extension to an old building can have a less damaging visual impact than inserting new windows in the visible envelope. Provided there is no particularly sensitive fabric involved, quite large openings can often be formed to link the original to the new addition.

Good design of the extension can bring in a lot of light that can be borrowed by the main building via the connecting opening. That could be achieved by incorporating a contemporary design with plenty of glazing, a lantern, skylight, light well, or even natural illumination via secondary sources such as sun tubes.