Solar Thermal Panels Explained – Your Guide to Solar Hot Water Costs, Pros & Cons

Solar thermal panels (also commonly known as solar water heating or solar hot water collectors) make efficient use of the sun’s energy to provide renewable hot water for taps, showers etc around the home. Solar water heater systems were the original solar panels, gaining popularity in the UK decades before their electricity-generating cousins, solar photovoltaics (PV).

Solar PV, of course, has soared in recent years, most notably since 2010, when its popularity was boosted by the government’s more-than-generous Feed-in-Tariff scheme. While solar PV shows no sign of letting up, solar thermal panels haven’t had anywhere near the airtime.

Is Solar Thermal Worth the Money?

Previously, solar thermal was supported by the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI), which paid out 22.65 pence per kilowatt-hour (kWh) of heat generated by domestic installations. The RHI, however, closed to new applications in March 2022.

The Boiler Upgrade Scheme (BUS) has since launched, supporting heat pumps and biomass boilers with government-backed grants. The casualty in all this is solar water heating, which is not supported by BUS. This is unfortunate, as solar hot water is a lower-cost option than other renewable technologies. What’s more, we are better at insulating our homes than we used to be – which means there’s less demand for space heating. As a result, the proportion of heating required for domestic hot water (DHW) has gone up.

So, the big question is whether solar thermal panels are still a worthwhile investment for self builders and renovators, despite the withdrawal of the RHI.

Solar thermal panels cost around £4,000-£8,000 to be installed in the UK – so do they still make sense cost-wise for self builders and home renovators? In this article, we take a look at:

- Your household’s hot water demand

- The proportion of heat energy used for water heating versus space heating

- Energy prices

- What backup heat source you’re using

- Whether you’re installing solar thermal in a new home or as a retrofit

- How much solar thermal panels cost to install

- The potential payback period for solar thermal panels and how much you can save

- If there are any subsidies for installing solar thermal panels

What Are Solar Thermal Systems & How Do They Work?

Solar thermal panels capture energy from daylight and repurpose it to generate free hot water. To work effectively, they should be installed with a southerly aspect (anywhere south of east to west should make a useful contribution; but north-facing is off the cards). The panels are typically installed on pitched roofs but can also be fitted to flat roofs or ground mounted. In many cases, they can be installed under permitted development (without the need for full planning permission).

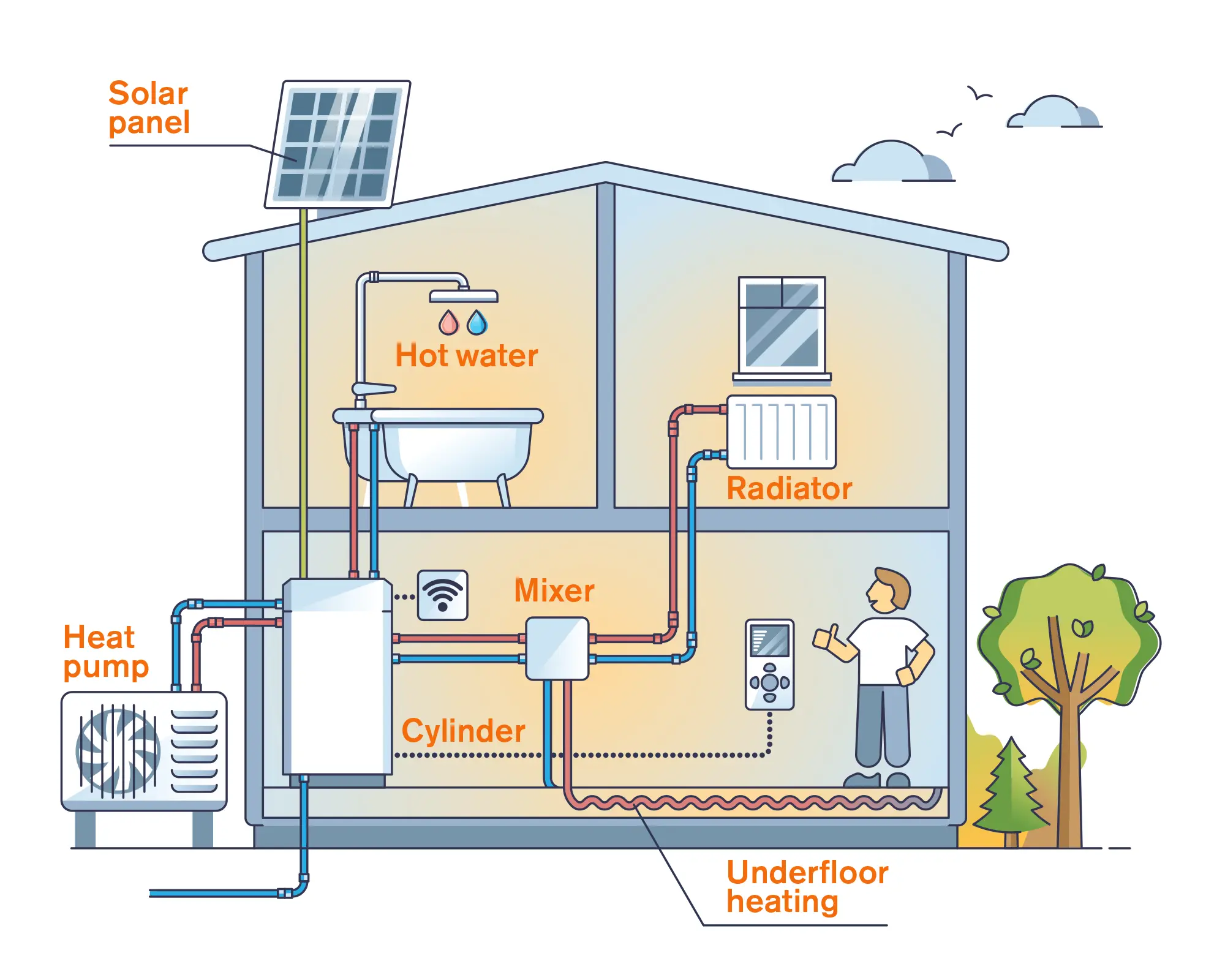

Photo: VectorMine / Shutterstock

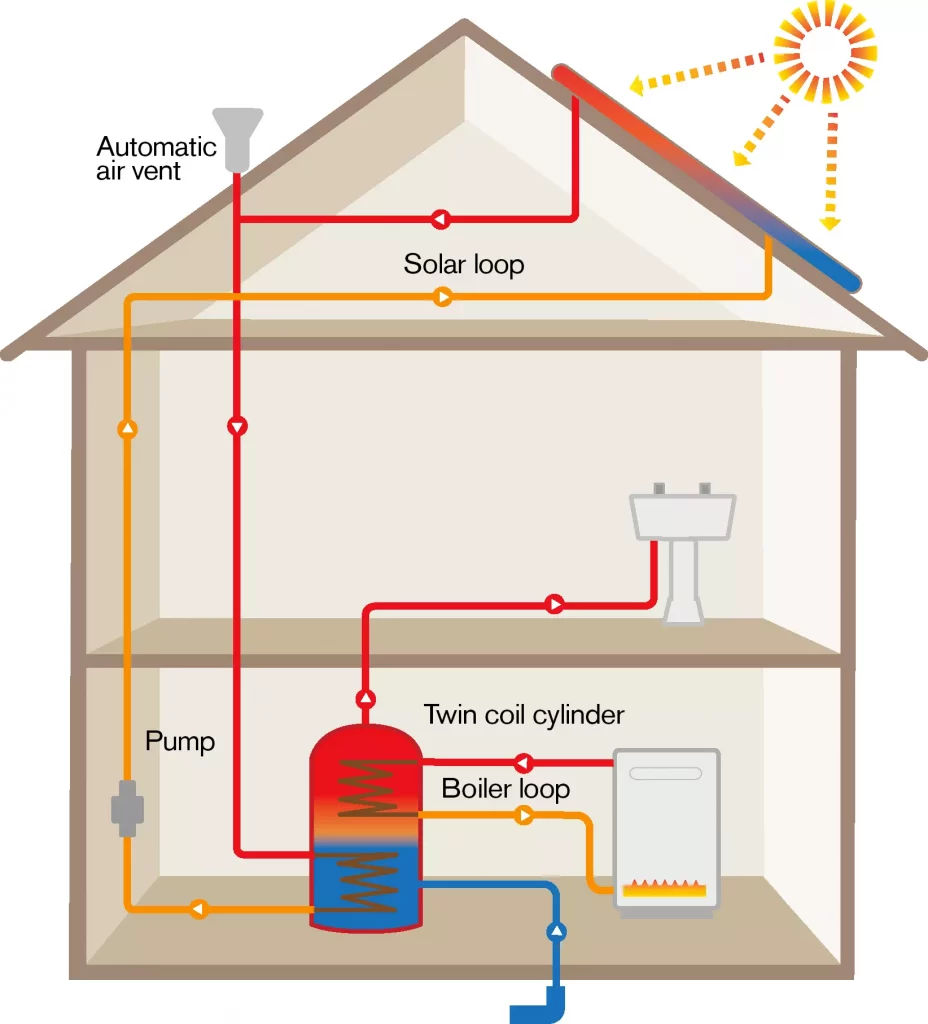

Most solar thermal systems are indirect; essentially, solar energy is trapped within the panels and transferred into a glycol-based heat transfer fluid, contained within a closed loop circuit. This then feeds into a dedicated coil inside your home’s cylinder, where the warmth is transferred into your hot water supply. So, the collector fluid itself never mixes with the output that goes to your taps.

A closed-loop arrangement requires a twin-coil hot water cylinder, where the secondary coil runs off a boiler, air or ground source heat pump or other source. There will also be an electric immersion backup, but this shouldn’t be needed if the system is designed and controlled effectively.

The key components of a solar water heater are the collectors (the panels), a twin coil hot water cylinder and a controller.

Types of Solar Thermal Panel Collectors

Two main types of solar thermal collectors are in common use – flat plate and evacuated tube.

- Flat plate versions normally have a Perspex cover mounted over an absorptive panel, through which the collection fluid is pumped. The whole unit is insulated below and at the sides.

- Evacuated tube collectors comprise one tube contained within another, with a vacuum between the two. The vacuum allows the radiation from the sun to pass through to the inner tube (containing the collection fluid) while reducing heat loss.

Twin-Coil Hot Water Cylinders

In a solar thermal setup, the hot water cylinder has two sources of heat – the solar coil and the boiler coil. Hence, it is known as a twin-coil hot water cylinder. As heat rises, the base of the hot water cylinder is normally cooler than the top. The solar coil is therefore located near the base of the tank where it is coolest, to make the best use of whatever solar resource is available.

There’s often an electric immersion backup fitted, but this should not be needed if the controls are set effectively.

Is My Hot Water Demand Big Enough for Solar Thermal Panels?

If you live alone or shower infrequently, the amount of hot water you need is likely to be minimal. What this means is that the cost of fitting a solar hot water system is unlikely to be a worthy investment.

Just as importantly, in this scenario the environmental impact of installing a setup might not be repaid either. So, it’s important to do the calculations before you start talking to installers.

This diagram shows how a solar thermal system functions in the home and generates hot water for your domestic use

If, on the other hand, your household is a family of four or more and everyone is showering daily, your demand for hot water will be very high, with similarly increased demand for washing machine, kitchen and sink use.

This means that the fixed price of installing a solar thermal system will be spread over a much larger overall demand, which of course means this would be more cost-effective. So, put simply, the higher your household’s hot water demand, the better value for money solar water heating will be.

What Size Should My Solar Thermal System Be?

The size of your solar thermal system comes down to your household’s hot water demand and usage pattern, but the starting point is about 1m² of collector per person living in the building. Most panels are 2m² to 3m², so a small household might make do with one, while a home with four or more people would generally need two panels, and so on.

Of course, it’s not just the collectors that need to be sized up: you’ll also need the right twin-coil cylinder capacity. As a rough benchmark, according to the Hot Water Association, a typical four-person household uses around 200 litres of hot water per day (based on average consumption). Because of the way a solar system works, however, this doesn’t directly translate to cylinder size.

A two-panel, in-roof flat plate solar thermal collector system from Grant was installed in this extended five-bedroom house, alongside a 300L twin coil hot water cylinder

The solar coil enters the cylinder at the bottom, so that it can heat the whole height of water in the tank. Meanwhile, the secondary coil (for your boiler or other heat source) typically sits about halfway up – this can only warm the water directly above, in the upper portion of the cylinder. The cooler water at the bottom is known as the dedicated solar volume (DSV), as it is exclusively available to be heated by the solar collectors.

Your installer should calculate the appropriate twin-coil cylinder capacity. As a rough guide, most households will need a 200-350 litre tank. The dedicated solar volume is determined by the entry point for the secondary coil, which is typically somewhere in the middle. So, a 300 litre cylinder might have 150 litres of dedicated solar volume.

Are there any subsidies for installing solar thermal systems?There’s currently no grant or loan funding available for homeowners to install solar water heating in the UK. The Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) closed to new applicants in March 2022, while the ill-fated Green Homes Grant – which trade body Solar Energy UK reckons supported 15% of all solar thermal projects – went pop in March 2021. MCS data suggests the loss of this funding has had a significant impact on take-up: in the 12 months prior to the cut-off date, there were 7,296 MCS-registered domestic solar water heating installations. In around a year, the body certified just 331 projects. Some of this drop-off might be because homeowners no longer see the need for MCS certification. The RHI was replaced with the Boiler Upgrade Scheme (BUS), which provides cashback payments of up to £7,500 on qualifying heat pumps and biomass boilers. As yet, there’s no place on the BUS for solar thermal. However, solar is eligible for the government’s temporary zero-rating for VAT on installing energy-saving materials. The scheme applies in England, Scotland and Wales and is due to run up to 31st March 2027. |

Space Heating vs Hot Water

Well-designed and insulated modern housing should have a very low space heating demand. So, in newer homes, domestic hot water forms a higher proportion of heat energy use than it does in older buildings. If you’re self building, you therefore have greater freedom to focus your attention and investment on driving down the running and carbon costs of your hot water demand.

That could lead you down the path of solar thermal panels. In fact, we’d argue if you’re self building a new family home, in most cases solar water heating is even better value-for-money than it used to be.

High-efficiency Vitosol 300-T evacuated tube solar thermal collectors from Viessmann

How Much Hot Water Can Solar Thermal Panels Produce?

In the summer, a well-designed solar thermal system should fulfil most of your family’s hot water requirements (90%+). Over winter, its contribution will dwindle to more like 25%, but it will still provide energy-saving pre-heating even on dull days. Across the year, a well-designed setup should provide about 50% of the total energy required to meet a household’s annual hot water demand.

This percentage is known as the solar fraction. Clearly, the higher this figure, the more free water heating you’ll get and the lower your energy bills. In practice, even the highest-performing and most efficiently-used solar hot water systems cap out at about 60%.

Performance-wise, a lot depends on usage. Ideally, your hot water will be timed so the boiler only fires before high-use periods (eg in the evening) and turns off again before you start consuming the hot water. This will give the solar panels maximum opportunity to replenish the full cylinder. If you leave the boiler feed running, it will heat the top section of the tank and leave only the dedicated solar volume available for the panels.

What Does a Solar Thermal System Cost to Install?

According to the Microgeneration Certification Scheme (MCS), a domestic solar thermal system cost an average of £5,921 to be installed in the UK in 2023. That’s a cost of £767 (15%) up on average 2022 prices – no surprise given inflationary rises in materials and labour costs – but it’s still around 10% cheaper than in 2021.

Your own solar thermal quote will depend on the size of solar system you need and the property it’s being installed into, but at present the scale is likely to run somewhere between £4,000 and £8,000 (including the twin-coil cylinder).

Solar collectors come in two main types: flat panel or, as shown in this illustration, evacuated tubes. The latter can provide a slight efficiency boost, but are generally a touch more expensive. Photo: iStock/KangeStudio

How much the solar thermal collectors cost themselves will be the same whether you’re retrofitting or installing panels into a new-build home. Beyond that, things start to diverge. On a new home, you’ll likely already have scaffolding in place, the roofer can leave a clear zone for the solar hot water panels, and there will be easy access for plumbing. You’d also have been buying a hot water cylinder anyway – so upgrading to twin-coil won’t be too much of an imposition.

If you’re adding solar thermal to an existing house, all of those elements become an additional expense. Plus, you’ll almost certainly already have a standard hot water cylinder, so in terms of return on investment, you’ll feel the full cost of replacing it with a twin-coil version.

How Much Money Will I Save with a Solar Hot Water System?

How much you can actually save with solar thermal panels will depend on your hot water demand, what fraction of it the solar system is designed to satisfy, and how you use it. Based on field trials and current energy prices, The Energy Saving Trust (EST) suggests a 4m² system (for a four-person household), might achieve annual savings of £95 versus a gas boiler, £130 compared to oil-fired heating, and around £180 versus electric water heating.

So, a £95 annual saving on a £4,000 system equates to a payback period of around 42 years versus gas (31 years for oil; 22 years for electric). But if you have a high hot water usage (or a swimming pool), and the setup gets closer to 60% of demand, the payback time tumbles.

If you’re thinking an air source heat pump (ASHP) could be a better bet, note the EST currently thinks this tech costs £20 more per year to run than an A-rated gas boiler for space heating and hot water combined; and ASHPs aren’t as efficient as boilers at producing hot water.

Energy prices have a major impact – the gas unit price cap is currently 5.48 pence per kilowatt-hour (p/kWh). But not too long ago, we were at 7.42p/kWh (35% more). At that price, payback would be more like 27 years versus a gas boiler. Solar thermal is a simple technology, too, requiring relatively little ongoing maintenance, whereas other renewables might involve more upkeep costs.

You may not be purely motivated by financials. The EST puts carbon savings from a 4m² solar water heating system at around 380kg per year versus a gas boiler, and 550kg per year compared to oil. These reduced carbon emissions can all add up on SAP ratings and other software used to inform planning and Building Regs requirements; so you may be able to further improve payback through money saved elsewhere on a project.

This article was originally published in October 2022 and has been updated in February 2024 to reflect updated costs and information. Words by Chris Batesmith & Nigel Griffiths.

Login/register to save Article for later

Login/register to save Article for later

Comments are closed.