Tudor-Style House Design Guide

Striking in design and frequently copied, the Tudor style dates back to the 16th century where it shaped construction techniques in the UK.

Homes were now built from timber and wattle and daub, where they had previously been made from cob or unbaked earth.

Tudor style checklist

|

The appearance of Tudor buildings reflects the way in which they were constructed, rather than being a result of the builders trying to impose a style. So, if you want your new home to have an authentic appearance, you must appreciate the limitations of the materials and technology used to create the originals.

How Tudor homes were built

Traditionally, oak was the main source of timber for construction. Tree trunks were used to make posts and beams, and the thicker branches made up the rafters to support the roof.

Unseasoned (green) timber was generally used for the main structure because it was softer, which with the tools available, was easier to work. Seasoned wood – timbers that have been left to stand for up to 18 months – was reserved for doors, windows and staircases. In contrast to the way that they are presented today, the frames were rarely painted black. The majority were left unfinished or possibly whitewashed.

A crucial part of the construction of a traditional frame is the way that the timbers join together. If this is not done skillfully with a tight fit, the joint will not transmit loads through the structure and it will sag or twist. Without the benefit of the effective metal connectors that we have today, the joints had to be carved out of the timber itself and pinned together with wooden pegs, or dowels. As the timber dried and contracted, the joints tightened and the structural link became more effective.

Roof pitches were steep because they were generally covered in thatch, which needs an angle of at least 45°. Dormers are often found on Tudor houses, although many of these were later additions.

One innovation that developed as construction methods improved was the jetting of the upper floors, where each level cantilevers up to two feet beyond the floor below. This allowed precious extra space to be gained above roads in crowded towns.

Types of frame

The vertical posts that form the walls were built off a plinth of stone or brick to raise them above the damp ground. The main skeleton of these houses can be divided into three types: cruck, post and truss, and aisled. These structures are lined up into equally spaced bays.

A cruck frame was created by splitting a large curved beam into two, leaning them onto each other, and then using a horizontal tie beam at a high level to hold them together. Using this method, a series of strong triangular frames were created, and erected in a line of bays that support an overhead beam running along the apex, or ridge.

A post and truss or ‘box frame’ represents an evolution from the very earliest homes built from vertical logs, and consists of a series of regularly spaced posts that make up the structure of the main walls. At eaves (or gutter) level they support a continuous length of wood or wallplate onto which the main sloping rafters sit. The rafters are held in place by horizontal tie beams that secure at each end and prevent the roof from spreading. This combination of rafter and tie beam, forming a triangle, is referred to as a roof truss.

These construction principles are still used today by oak frame suppliers. It can be summarised as the construction of a free standing framed timber box, onto which a roof is placed.

A variation on the types already mentioned is the aisled frame. Because timber roof trusses could only span limited distances without spreading outwards, medieval builders came up with the idea of bracing the sides of the building to prevent this effect. Initially this meant that posts were needed at each end of the frame, but later a more sophisticated construction known as a hammer beam was developed which eliminated the need for them.

Traditional Tudor materials

The spaces between the timber posts were often filled with ‘wattle and daub’ constructed by the use of thin oak uprights or ‘staves’, which are interwoven with hazel strips to form a rigid panel. This was then plastered with a mixture of clay, dung and chopped straw and left to dry. To protect it from the weather, it was whitewashed. If properly constructed and regularly maintained, this simple construction can remain in good condition for centuries.

Later in the 16th century brick cladding was used, but proved less reliable because it could not move with the timber. As the main timbers shrink, cracks open up around the dimensionally stable infill panels, letting in the damp. Other alternatives for covering infill panels introduced as later modifications include tile hanging and stucco, which is made of plaster, or lime mixed with sand.

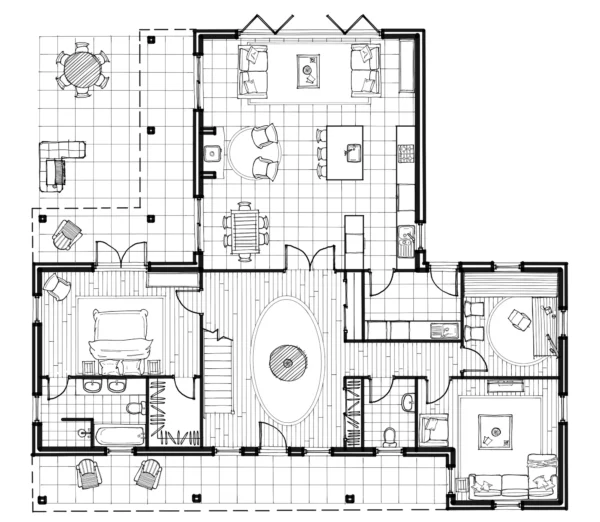

Internal layouts

The central feature of a Tudor house was a large hall with an open roof, which was originally the only room, first floors often being added later in the period. Oak was not available in straight lengths beyond 6m, which limited the width of the largest spaces. Corridors joining rooms were unnecessary as privacy was not considered important.

Town houses tended to be long and thin, presenting very narrow gabled frontages to the street. Houses built in the countryside, where there was more land, often presented their longest, pitched side to the road.

Case study: Tudor-style self-buildWhen the Moores realised their current home wasn’t meeting their growing family’s needs, they decided to knock it down and rebuild a larger property on the same glorious plot. They enlisted specialist oak frame company Border Oak to design and build a fabulous Tudor-style manor house, complete with a traditional facade and characterful exposed beamwork inside and out. Among the many fabulous heritage features are 15th-century style jetties and timber windows, updated to meet modern standards of energy efficiency. Read the full story here to find out more about the project, from design inspiration to build costs and what the house is like to live in. |

The interiors were practical and simple apart from the fireplace, which was made into a design feature with elaborate carving. Walls were clad up to dado height with vertical timber boards, and the floor beams were also given some carving.

Doors were formed from planks and topped with flat heads or, in grander residences, four centred arches.

Early in the period, windows rarely had glass and usually featured thin vertical bars called mullions. As glass began to become more readily available, bays and large windows at the end of the halls (made of many small diagonal or rectangular panes) were incorporated.

New house, Tudor design

‘Mock’ Tudor houses have been popular since they were introduced into the Arts & Crafts style at the end of the 19th century.

Elevations created by applying fake beams in the form of timber boards onto rendered walls can look authentic as well as attractive, and are seen throughout the UK. They are most successful when designed by someone who appreciates the heritage, understands the specialist construction methods that were used and ensures that the decoration is consistent.

Where boards are applied to a standard modern elevation without this knowledge, the result usually looks wrong – there is a lot more to the Tudor style than just the familiar black and white pattern.

The ideal way to achieve a feeling of authenticity is to use an oak frame supplier and have it built using similar techniques to those of the craftsmen of the 16th century.

Even if you do this, modern Building Regulations make it almost impossible to expose the structural timbers on both the outside and the inside, because they conduct heat out of the building and reduce its energy efficiency to below modern standards. This means that if the dwelling is to look like a Tudor house on the outside, either the posts cannot be put on display inside, or the pattern of external timbers has to be artificial.

Modern standards and Building Regulations therefore make some of the features of a Tudor house difficult to achieve, but with some ingenuity it is entirely possible to create a contemporary version that will make a pleasing and elegant home.

Main picture: This home was designed and built by package house specialists Scandia Hus

Login/register to save Article for later

Login/register to save Article for later

Comments are closed.